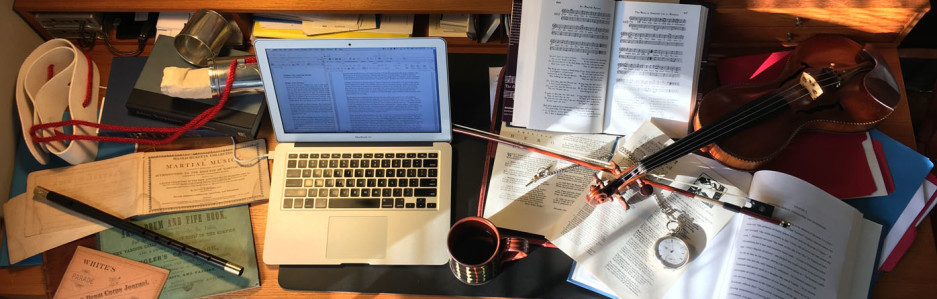

I have been engaged with education for more than forty years. My career began as a teaching musician and costumed interpreter for the public and with school children at Colonial Williamsburg. Over several years I assumed increasing supervisory and administrative responsibilities.

I have been engaged with education for more than forty years. My career began as a teaching musician and costumed interpreter for the public and with school children at Colonial Williamsburg. Over several years I assumed increasing supervisory and administrative responsibilities.

From 1985 to 1998, I directed Colonial Williamsburg Historic Area programming in various capacities including the Director of the Company of Colonial Performers; Director Historic Area Presentations and Tours; Director Historic Trades; and Director of Historic Area Programs and Operations.

From 1998 to 2010 I led Colonial Williamsburg’s K-12 education outreach initiative as the first Theresa A. and Lawrence C. Salameno Director of Educational Program Development. Concerned about the quality of history and civics education around the nation, I worked with a talented team to improve curricular materials, quality assessments, and teacher instruction in collaboration with states and school districts nationally.

I was named the Royce R. and Kathryn M. Baker Vice President for Productions, Publications, and Learning Ventures in 2011, leading the Foundation’s media production initiatives including book publication, video, audio, photography, www.history.org, the Colonial Williamsburg Journal, and the K-12 education outreach initiative.

In 2016, I left Colonial Williamsburg and worked as a freelance consultant, and author. I taught early American history and American Studies as an Assistant Professor Adjunct Faculty at Christopher Newport University in Newport News, Virginia from 2016 through the spring semester of 2023. I was also, during that period, Visiting Distinguished Scholar for CNU’s Center for American Studies.